‘Verifiable Parental Consent’

India’s new data privacy law, the Digital Personal Data Protection Act, 2023 (“Act”), is expected to be implemented in the coming months. One of the main changes proposed in the law is that data processors will be required to obtain ‘verifiable parental consent’ before processing children’s data.

Section 9 of the Act deals with the processing of personal data of children. A child is defined as any individual under the age of 18 years. Section 9 requires certain compliances of a ‘data fiduciary' (data processor) under the new act dealing with children's data:

- before processing any personal data of a child, the data processor should obtain verifiable consent from the parent or lawful guardian of the child,

- they should not undertake such processing of personal data that is likely to cause any detrimental effect on the well-being of a child, and

- they should not undertake tracking or behavioural monitoring of children or targeted advertising directed at children.

2025 Draft Rules Add Some Clarity

On January 3, 2025, the Indian Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology ("MEITY") released draft Digital Personal Data Protection Rules, 2025 ("Draft Rules") under the Act. Draft Rule 10 of these rules provides some additional details on what is required of data processors.

Rule 10 of the Draft Rules states that data processors are required to adopt appropriate technical measures and observe due diligence to check that the person identifying themselves as the parent of the child is an adult. The Rule goes on to state that the identification of the parent can be checked by reference to:

(a) reliable details of identity and age available with the data processor; or

(b) voluntarily provided details of identity and age or a ‘virtual token’ mapped to the same, which is issued by a regulated entity, and includes details or token verified and made available by a ‘Digital Locker’ service provider.

As such, the Draft Rules clarify that a data processor can determine the identity of the ‘parent’ by referring to their own records or the records kept with an authorised entity, such as a virtual token provider.

Virtual Token Based Identification

The move to allow parental verification by using virtual tokens does have its merits. India’s national ‘Aadhaar’ ID system is fairly widespread (with over 1.3 billion unique numbers generated), and can form the backbone of a token based ID system.

Following the notification of the Draft Rules in early 2025, the MEITY passed an amendment to the Aadhaar Authentication for Good Governance (Social Welfare, Innovation, Knowledge) Amendment Rules, 2025, dated January 31, 2025, to enable “any entity” to apply to perform Aadhaar-based authentication. Considering that private entities can now also be authorised for using Aadhaar to deliver their services, it is possible that this is aimed to serve the purpose of age verification by data processors.

Virtual tokens are not new to the Indian digital ecosystem. A few years ago, the UIDAI had introduced the concept of Virtual IDs (“VID”). A VID is a 12-digit biometric number mapped to the Aadhaar of a particular user. VIDs can be used for performing authentication without providing their full Aadhaar numbers.

Some Roadblocks Remain

The requirements under the new Act are aimed at protecting children’s personal data; that said, its requirements do present a few practical hurdles.

For example, data processors may have to collect excessive personal data, not only of children (who are possibly their ‘main’ data subjects), but also that of their parents. To prevent non-compliance, data processors may resort to a protracted verification exercise for each ‘user’ to ensure that they are adults. This will increase the compliance burden, and take away from the Act’s larger principle of ‘data minimisation’.

With respect to the VIDs in this context, there are a few hurdles to overcome as well. The user is required to generate VIDs themselves, which can be challenging due to the comparatively low digital literacy in India. A VID or biometric number also stays ‘active’ until such time a new one is generated by the user, which could lead to security issues if deployed for age-verification across platforms. In this regard, this system may need clear guidelines on how virtual tokens can be generated, who will generate them (keeping in consideration digital literacy concerns), and how they will be secured.

Obtaining parent’s consent is an important step towards protecting children’s personal data and their use of the Internet. Finding a workable and scalable method to obtain parental consent will ensure that children’s access to the online world is not curtailed, once the new Act comes into force.

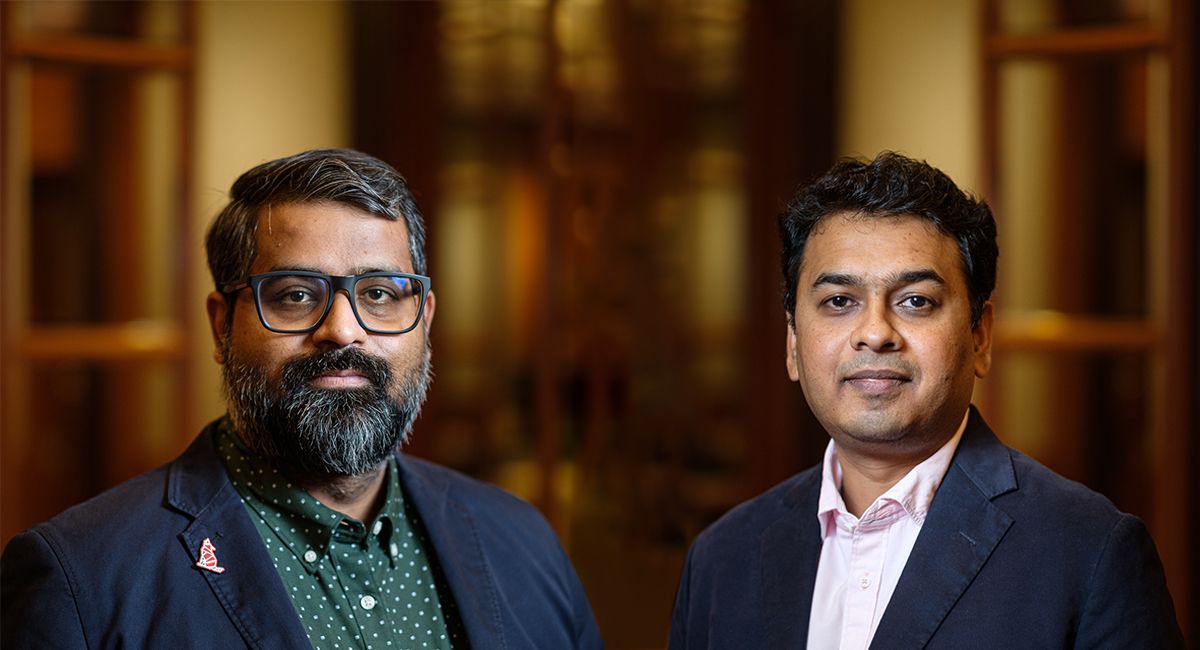

Article provided by INPLP members: Vikram Jeet Singh and Prashant Mara (BTG Advaya, India)

co-author: Arushi Mukherji

Discover more about the INPLP and the INPLP-Members

Dr. Tobias Höllwarth (Managing Director INPLP)